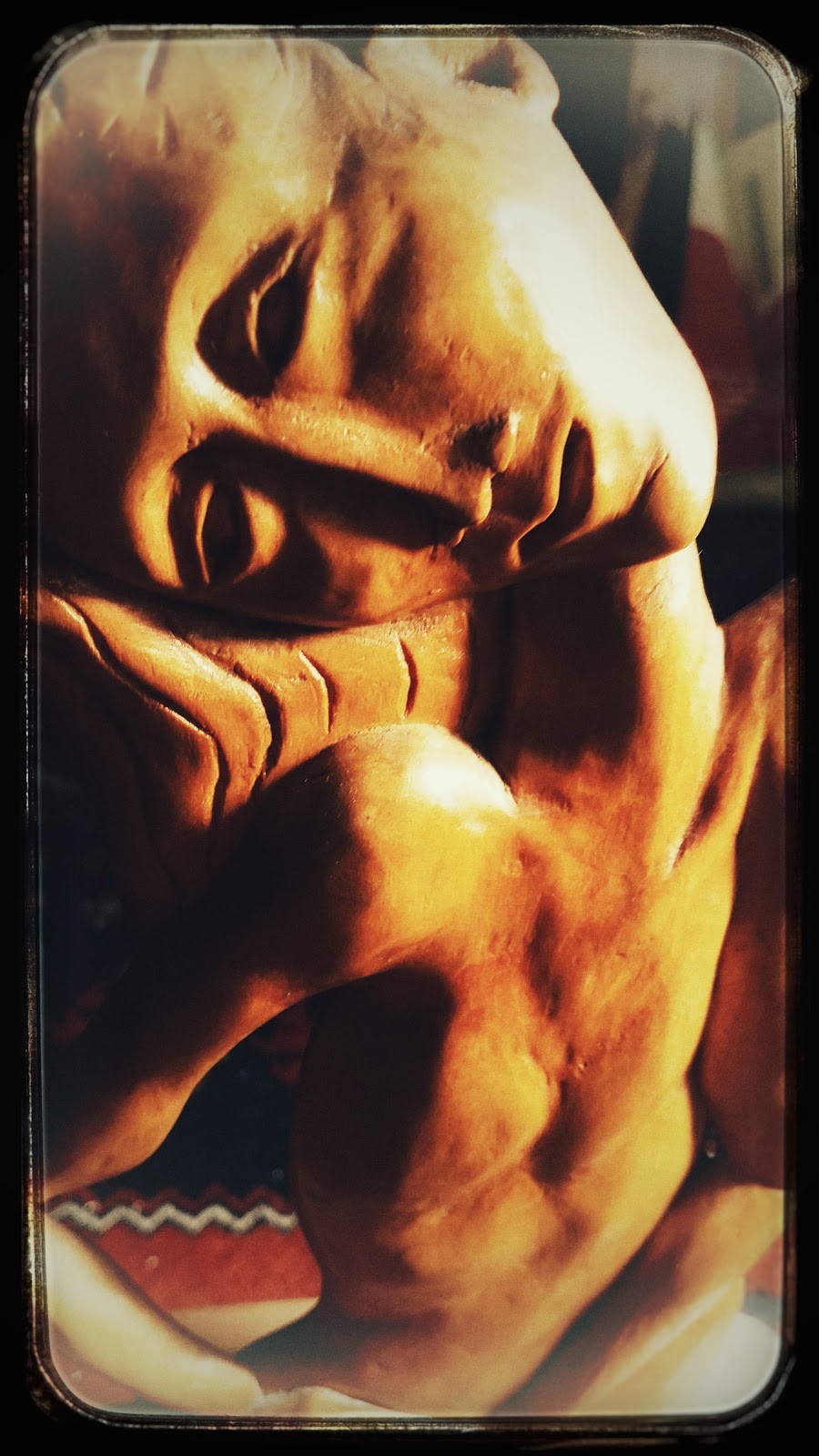

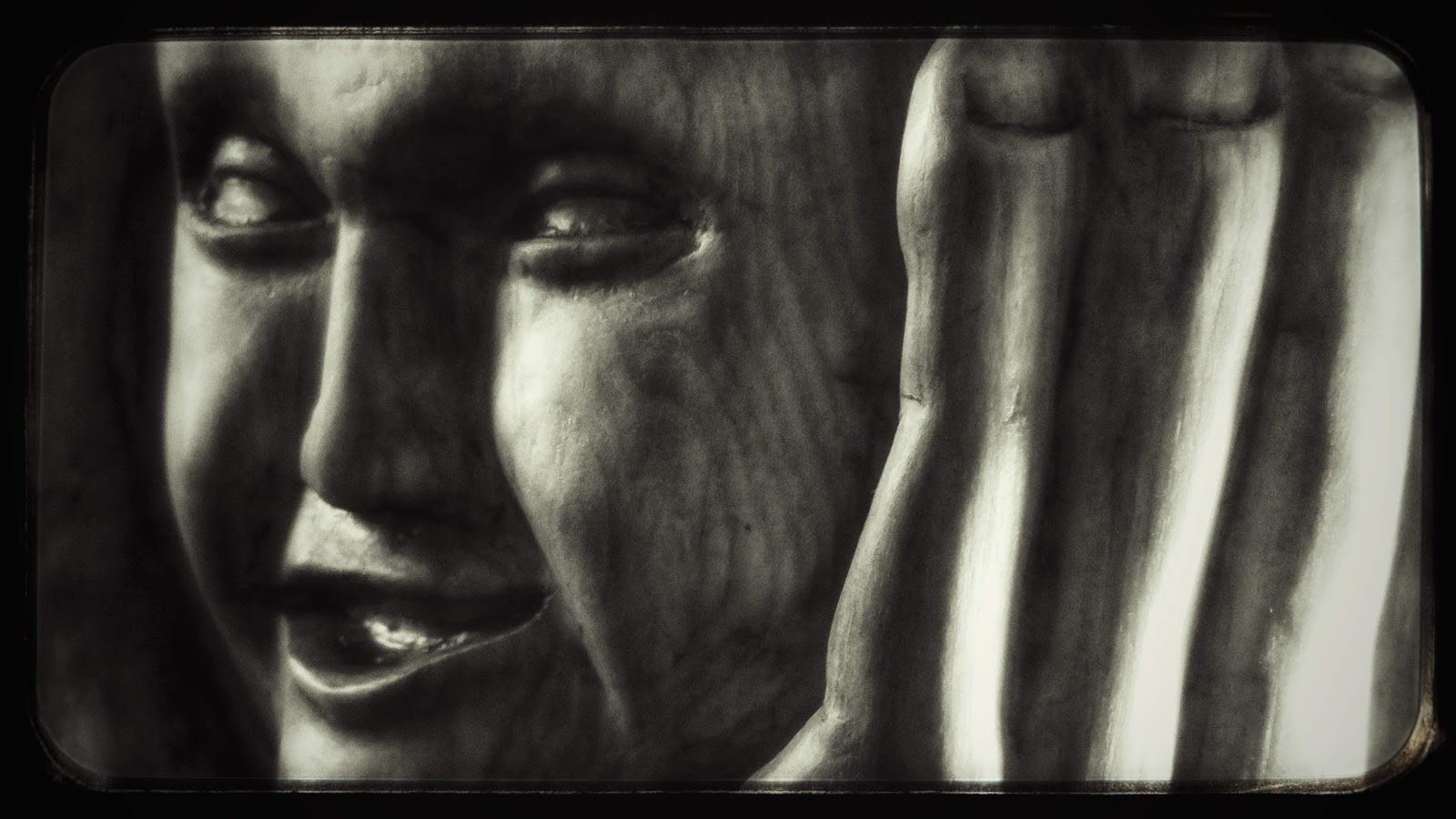

This article is an excerpt from my forthcoming book: "Artists Mentoring Artists" Tim has been a mentor to me for years, and took the sculpture portraits I'm using on this site. Tim Byrne Photography

Tim Byrne: Humbleness and questions

Mentors are not gurus. They do not dump data. They do not

tell people what to do. They are not wed to their own opinions. They do not

know it all. They ask questions born of genuine curiosity about their mentees,

and desire to help them expand their work.

Tim Byrne is such a mentor. He roots his mentoring in

humility, high interest in and admiration of other people, and skill at asking

questions to draw out their talent and confidence.

I met Tim when I started my management consulting business.

I joined the Chamber of Commerce, and he was the first person to welcome me. He also

immediately started to mentor me. He learned about my business by asking me

thought provoking questions. He introduced me to resources, offered to edit my

marketing materials, encouraged me to become involved in projects that

showcased my skills, he advocated for me. He lives to help people, and he has helped

me a great deal. He still mentors me, now focused on my sculpting and related

business challenges. I’m always energized, enlightened and inspired by talking

with him.

Tim mentors: it’s just what he does. Why? He says “I’ve been

blessed through my whole life with good teachers. I knew early on that I wanted

to be a teacher, and that’s been my slant on my entire career. I’ve been in

sales, marketing, and now professional photography. It’s all about teaching, and good teaching is

mentoring. All mentoring is mentee-focused.”

Tim now works with both aspiring and experienced

photographers. He’s taught classes and mentored in many settings for many

years. He says it’s no different than mentoring at Proctor and Gamble, where he

learned about formal mentoring. There, everyone was expected to get mentored

and be a mentor, as well. He believes that everyone needs a mentor, whether pursuing

corporate or artistic goals.

If you want to be a successful photographer, you need to

learn three sets of skills: technical, artistic and personal. Tim says “Photography is a people business.

For instance, you have to be able to build a relationship in seconds when doing

portraits or model shots. You need to be able to click with the subject quickly

in order to capture a likeness that truly reflects that person. I’ve worked

with President George W. Bush, I’ve worked with school kids. It’s all the same process.

Even if you’re not taking photos of people, you still need people skills to

deal with customers and potential customers.”

Beyond the personal skills, photography is a “Gemini

business. It’s artistic and technical both. Tim mentors aspiring professionals

on the realities of the business. Taking photographs is about five percent of

the activity. The other 95% is processing, marketing, finding the next shoot.

This is not the glamorous business that mentees often think."

How do you get your work to come out in a predictable and

repeatable manner? Tim: “Dr. W. Edwards Deming talked about a predictable

course of improvement. When I mentor people, they must want to get better,

regardless of their current skill levels. We can all get better. We need to be

strong enough to boldly look at what’s wrong with our work, in addition to

what’s right with it, within ourselves and the wishes of the marketplace.” People need to be pushed to conquer their

fears. Tim is very afraid of heights, yet he often shoots from extremely high

places. He has pictures to prove it. His mentees frequently dread taking photos

of people. They must learn to overcome that reticence by just doing it, so he

assigns photographing people to those mentees, patiently encouraging them.

I asked Tim how he approaches

this three-tiered photography mentoring- technical, artistic and personal. Does

he cover all three aspects at once? Does he assess mentee strengths and

weaknesses and choose an area to focus on? Does he start with one and build on

that towards mastery of all three? His response, “I don’t choose what aspect to

focus on, my mentees do. I help them decide by asking questions. The mentee

drives the entire process, I teach them how to think about it. There are six

basic questions that I find myself asking all the time. No matter what quality

of work someone presents to you, never say that’s bad or good. Instead, get

them to analyze themselves:

1. What

are you trying to do?

2. Where

have you succeeded/not?

3. How

will you improve?

4. How

do you plan to get to your goal?

5. What

happens if you don’t get there?

6. What

happens if you do get there?”

The last question is an unusual one. Tim says “a lot of

people fear success. It changes our world in ways we don’t know about yet. We

all know what it’s like to fail, because we all fail. How many successful

athletes and other celebrities go on benders or go bankrupt? They don’t get

guidance on how to manage success.”

Tim doesn’t want to create “little Tim’s,” even though

mentees may ask him to judge their work. He does mentoring in portions that the

mentee can easily welcome. “It’s like doing figure work. The models let me into

their space; the mentees need to let me in, as well. Then the mentees can say

their dreams and their weaknesses, and I can help them chase those dreams and

build on those weaknesses. I can’t tell them what to do, because then I’d be

holding mentees to my own limitations. It’s not the world according to Tim.” In

classes, students will bring photographs, asking Tim to give his opinion right

away. Tim says “Neat. What were you trying to do? What techniques did you use

to do it? How did you accomplish what you did? Are you pleased? Why? How are

you benchmarking your work? What will you do differently next time?” This opens

people up to the process of self-evaluation, and removes Tim from being either

the bad guy or the genius. He teaches them to think, and to feel like they’re

improving. He wants to keep the process of development going, keep the

conversation going. Tim says he doesn’t have the credentials to “preach”

artistically, so he doesn’t give that kind of advice. He is not formally

educated as a photographer. He reads, looks at others’ work, and often refers

mentees to other resources. I just brought a work-in-progress carving to Tim to

document my process. He examined, and was reminded of a painter who portrays

action using techniques that are similar to the grain of this wood. He right

away showed me the artist’s work on the Internet, to stimulate new thinking.

Not surprisingly, Tim has had mentors who’ve helped him

become a successful as an artist and business person. He currently has a

co-mentoring relationship with another local photographer. They are both

members of the Maine Professional Photographers Association. They get together

before competitions and critique each other; their markets are very different,

so they are only nominally competitors. They share projects, are good friends,

trust each other, and “tweak” each other. They even mentor each other about the

business, within allowable legal limits. One challenge is dealing with the

“ipod photography club,” people who take

their own special event photos with their camera phones. Tim says this is not

good photography, but it does impact the professional business.

Tim partners with other photographers and visual artists

whenever possible. He is dedicated to his own learning as much as that of

others. He knows that being a good mentee is precedent to being a good mentor.

He has the humbleness for both.